GHOST KILLER opens with a statement of intent, a darkly lit alleyway, enter the performers, as on a stage, Mimoto Masanori’s character Kudo fending off three masked assailants, only the sound of the fight, bladed weapons whooshing, grunts, fabric crackling and feet against pavement, creating a soundtrack of its own. The participants move in the now typical but still exciting way of a Kensuke Sonomura fight; hunched, always on the guard, undulating, searching for an opening, quick bursts, try-out like attacks, before finally finding a way to get through. There’s a low gravity, tied to the ground flow and tied to this motion is the longer undisturbed takes, in which you can clearly follow this ebb and flow. Instead of the now so recurrent and obnoxious whipping motion of the camera following every hit or fall to underline its impact, GHOST KILLER captures its action in long shots with smooth camera movements. Instead of abruptive camera and editing work which draws attention to the artificiality of the surface Sonomura leads the eye towards the bodies in motion.

Visually Kenuske Sonomura’s approach seems informed by that of action director/choreographer Lau Kar-Leung and classic Hollywood musicals.

The groundbreaking work of Donnie Yen and crews on SPL (2005) and Flash Point (2007), as well as Yuji Shommura’s RE:BORN (2016) and combat supervisor Yoshitaka Inagawa’s real close-range knife combat based techniques is another junction In both style and choreography that heavily informs Kensuke Sonomura’s work.

Of course an alleyway setting in itself will lead the thought to SPLs counterpart, in this ever influential fight scene between Donnie Yen and Wu Jing improvisation held a large part in the excitement of its depiction. Something Sonomura seemed to lean heavier into in his last movie BAD CITY, where a looser, “brawly” was mixed in with the heavily stylized choreography.

This unobtrusive approach to camera placement and editing, to capture the performance, also carries another implication to Sonomura’s intent; to show the strategy and quick on the feet adaptability of the fighters. The way the action is captured gives a glimpse into how the fighters adapt, change, readjust, try out motions before doing them full force, is such an exciting and rich visual concept. It is both reminiscent of contemporary dance for the stage and of tense fight scenes with actual stakes.

CLINCH, a dance performance choreographed and performed by Àngel Duran, touched on similar ways to capture fighting inspired movement, in which the dancers through positioning and tempo shift illustrates camera placement and editing. It focused on the intimacy of the fight scene, depicting both violence, beauty and tenderness and attraction. Kensuke Sonomura achieves similar tension and urgency in his depiction of combat and physicality. This cinematic and theatrical stylisation in understanding with the negligible difference between theatre and filmatic expressions approaches the authentic.

So when finally reaching the end fight between Mimoto Masanori and Kawamoto Naohiro all this comes together in a blistering display. All these considerations that have been presented in ever more elaborative fashion throughout the movie’s fight scenes come to full fruition and are expanded upon. Two on screen performers of impressive capacity finding and measuring each other, finding openings, retreating and advancing.

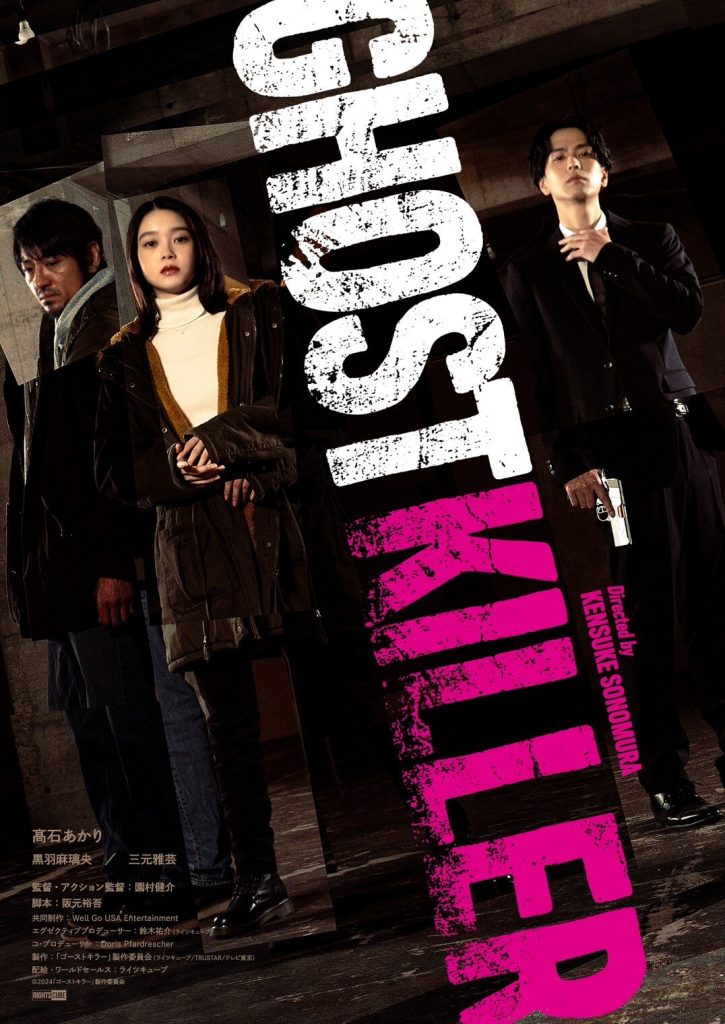

Takaishi Akari’s character Fumika is working in a restaurant, going on dates with weirdos and is just tired of it all. When she happens upon the bullet that killed legendary hit-man Kudo (Mimoto Masanori) she starts seeing his ghost and as it turns out can be possessed by him and thus perform martial arts. This odd couple ventures on a journey to try to investigate and solve his murder. Initially the movie does bear a resembling tone to off kilter low key indie action dramedy BABY ASSASSINS (Yugo Sakamoto, 2021). Unfortunately it can’t maintain that offbeat character driven tone and leans too heavily on exposition, often explaining things we are seeing and also doing it several times.

It drains it of energy, the initial 40 minutes where Fumika uses Kudo to wreck havoc on awful men, while well meaning, is a bit plodding, it does however suggest a set-up for a movie about a reluctant low key vigilante. However it chooses to shift course and focus on Kudo’s revenge part of the story, something that they should have possibly saved for a later installment.

In Kensuke Sonomura’s directorial debut, HYDRA, he showed some promise beyond that of capturing action. Between the setpieces it had brief moments of respite, lingering on the mundane, letting the camera breathe just a little bit longer on nothing in particular. Kensuke Sonomura showed an intuitive grasp for the gesture and at the hinted at, it opened up the movie for something less generic, moved away from cliché and wasn’t as strictly plot driven.

Or maybe I read too much into those aspects, maybe it was design by mistake, not having learned to edit tight enough, or maybe it really was a conscious influence from working with Mamoru Oshii on Nowhere Girl (2015), whose films are almost defined by a lingering on the urban landscape to establish tone. But this gentle attention to non plot detail has languished in subsequent films of his and streamlined narrative presentation to something less intriguing. The inelegant approach to story telling stands in stark contrast to the clarity of action.

Thanks to Anders Hultqvist check out Just another Action Anders here on X